By MARK WHITEHOUSE

Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

December 28, 2005

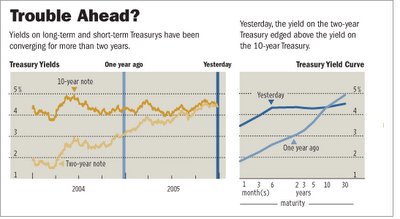

The nation's bond market interrupted the holiday season with a downbeat message yesterday: Many investors expect the economy to hit tougher times within the next year or so.

That pronouncement came in the form of long-term interest rates dropping below short-term rates, a trend that often -- but not always -- precedes an economic downturn. The development is known as an inversion, because it flips the traditionally upward-sloping shape of bond yields plotted on a graph. The yield curve typically rises because longer-term debt usually pays higher interest rates to compensate investor

s for the greater risk they incur waiting for repayment.

s for the greater risk they incur waiting for repayment.Inversions can squeeze or even eliminate profit margins for banks, hedge funds and any other financial business that borrows money at short-term rates and lends it at long-term rates. "This is a warning signal...that we are on recession watch now," says Paul Kasriel, chief economist at Northern Trust Co. in Chicago. The inversion, however, so far is minor, he says. And some economists believe an inversion isn't as reliable a predictor as it once was.

In late New York trading, the yield on the 10-year Treasury note, which reflects investors' long-term view of the economy and is a key benchmark for mortgage loans, had dropped just slightly below the yield on the two-year note, which tracks expectations for the Federal Reserve's monetary policy in the nearer term. The 10-year note's price was up ¼ point, or $2.50 for each $1,000 in face value, to yield 4.343%. The two-year note was up 1/32 point to yield 4.347%, and the 30-year bond was up 21/32 to yield 4.508%.

The bond market's gloom may seem incongruous, given that inflation remains under control and the economy grew at an annual rate of 4.1% in the third quarter, marking the eighth straight quarter of one of the most stable stretches of growth on record. Analysts cautioned against reading too much into the timing of the inversion, which came amid a dearth of economic or other market-moving news and amid thin holiday dealings. Still, it was the first inversion in five years, and many see it as a signal of bigger, sustained moves to come. It was also cited as a factor behind a weaker stock market yesterday. (See related article.)

"The big question is how dramatic [the inversion] becomes," says Thomas Girard, co-head of fixed income at Weiss Peck & Greer Investments in New York.

Bonds make fixed interest and principal payments to investors, but their yield depends on what the market is willing to pay for the bonds on any given day. In deciding what yield -- or return -- to demand on bonds, investors consider various factors, including their expectations for future short-term interest rates and the bond's duration.

Investors, for example, usually demand more yield from governments and companies to tie up their money in longer-term bonds. When they are willing to accept a lower yield, that means they are persuaded that the Fed, which most expect to raise short-term rates to 4.5% or higher early next year, will soon have to bring those rates back down to mitigate, or ward off, a recession. Yield-curve inversions have preceded all of the last six recessions, but have also sounded two false alarms, the most recent in 1998.

The housing market is the most likely trigger for an economic slowdown and Fed reversal. As the Fed raises rates, monthly payments on adjustable-rate home loans go up, cooling demand for houses and leaving homeowners with less money to spend on all the other things companies want to sell them. Second, as house prices stall, homeowners aren't able to borrow as much against the value of their homes -- a source of cash that has added hundreds of billions of dollars to consumers' spending power in recent years.

"What the Fed is going to do is shut down the ATM machine known as the housing market," says Tad Rivelle, chief investment officer at Metropolitan West Asset Management in Los Angeles. Fed policy makers hold their next meeting on Jan. 31, which is expected to be the last before Chairman Alan Greenspan retires, leaving the reins to Ben Bernanke, the nominee to succeed him.

The Fed's attempts to cool the economy, however, don't always provoke a recession, and many economists, including Mr. Greenspan, suggest that the yield curve might have lost its predictive abilities. That's because foreign buying of U.S. Treasurys and the Fed's success in controlling inflation have kept long-term interest rates unusually low, so U.S. consumers and companies still have relatively cheap access to money that they can spend on buying houses and building factories.

A recent study published by the Fed estimated that in the absence of foreign buying, the difference between two-year and 10-year yields would be about 0.75 percentage point greater.

"Many factors can affect the slope of the yield curve, and these factors do not all have the same implications for future output growth," Mr. Greenspan wrote in a recent letter to Congress.

But even if it doesn't presage recession, a severe and prolonged inversion can cause a lot of pain, particularly for banks and hedge funds that make long-term investments with money borrowed at short-term rates -- the so-called carry trade. Big banks such as Citigroup Inc.'s Citibank unit and J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. have already cited the flattening yield curve as a factor affecting profits, as the interest rate they must pay to attract deposits rises closer to the return they can expect on their investments. "You can't make it up on volume if you're borrowing at 4.25% and lending at 4%," Northern Trust's Mr. Kasriel says.

沒有留言:

發佈留言